All Tied Up in Neckwear

An Ode to the Necktie: Exploring the Evolution and Sartorial Relevance of this Iconic Menswear Symbol

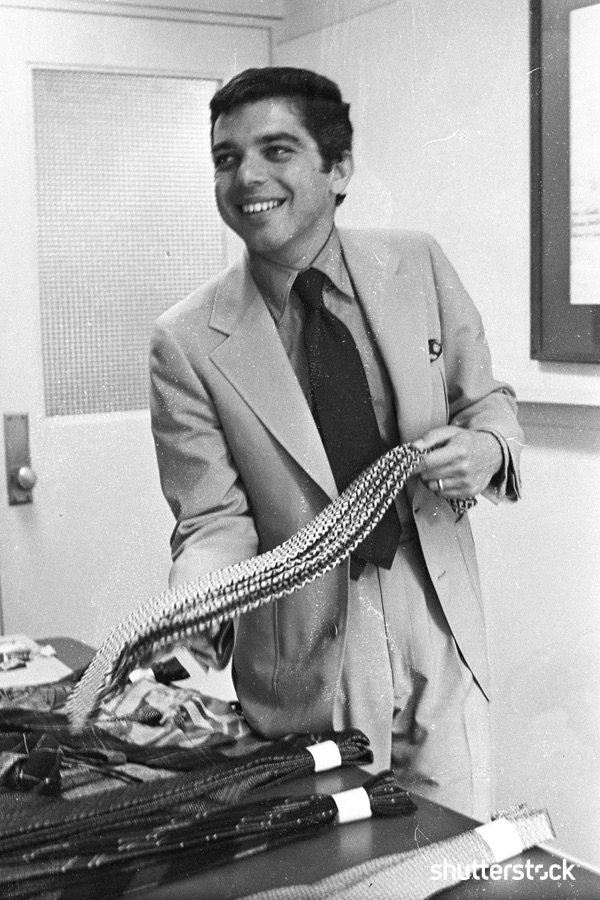

Courtesy of Peter Kuklinski, from his collection

Contributor Peter Kuklinski, aka the “man of cloth”, lives in Bala Cynwyd, PA and has been a part of the woven manufacturing textile industry for over 3 decades. Peter works for Valdese Weavers as a Regional Sales Manager in their NYC office.

ONE MAN’S JOURNEY

While attending the Philadelphia College of Textiles and Science during the early 1980s, I often frequented the Salvation Army thrift store in search of Harris Tweed jackets and thin neckties. I strove to play the part of an intelligentsia-minded glam rock dude who took his cues from Bryan Ferry while humming Joe Jackson’s “Look Sharp.” No pins, zippers, or spiked hair for me: just a cool, crooner-worthy tie beneath a pointy collar and a great jacket made my statement. And since a style-conscious, well-fitting jacket was more difficult to procure than interesting ties, I unearthed a multifaceted range of neckties in varied fabrics, chiefly from the late 1950s through the mid-1960s. Studying textiles, I became immersed in the variety of different fiber blends, colors, and styles that appeared in my small, but precious collection. This opened my eyes to the sartorial charms of textiles for menswear–luckily coinciding to some degree with my academic interests. And thus, my love affair with neckwear was born. Journey with me on a brief study exploring the tie throughout history, alongside its current-day relevance in the fashion world. Who knows? You might just be inspired to wear one.

Fast forward to graduation, I interviewed with two neckwear companies, but for various reasons neither one panned out. My first industry role came at Arc-Com Fabrics in Manhattan in 1984, a time when people still dressed up for work. Now that I had a real job, I wanted to be more adult-minded and look the business part, so to speak. Quite fortuitously, I happened upon an exceptional brand-new Charles Jourdan necktie at a remarkable price. It was a high-quality silk and its brand-new crispness was so much more than I was accustomed to from my thrift shop grabs. At 58” long with a 3.5” width coupled with a delicate weight, balance, and dapper design, I was seduced into a lasting respect for these knotted neckerchiefs.

Bryan Ferry of Roxy Music, 12th December 1975

NECKWEAR THEN AND NOW

In the 17th century, the French adopted and popularized ties from Croatian mercenaries who knotted linen and silk cloths around their necks (the French word cravate was an accidental mispronunciation of croate, meaning Croatian) in their home country. From there, the fervor for fashionable neck adornments spread around the world. In the Arc-Com studio, I noticed several neckties pinned onto inspiration boards for upholstery development, and this linkage to furnishing textiles was firmly cemented for me.

Fashion icon Ralph Lauren got his business start in the late 60s by pedaling his own custom-designed ties to men’s shops. Almost every man wore a tie somewhere during the mid-century, and many wore ties daily. Their popularity stretched into corporate apparel, schools, fraternal organizations, clubs, and, of course, the military. As one’s expression can be as unique as one’s fingerprints, an outspring of highly customized ties met the call for more unique ties, bringing famous artists to the table such as Salvador Dali, and later, Peter Max. Licensed masterworks from famous artists such as Picasso, Matisse, Van Gogh, and Klimt appeared alongside museum-licensed designs through the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian–all staples of neckties from those times. Neckwear aimed at favorite rock bands, sports teams, kitsch themes, even political identities, were a part of the novelty neckwear landscape. Again, a personal connection to art and design was obtained through the discriminating use of neckwear.

As we begin 2023, neckties head into the year with a continued flat outlook compared to the popularity of previous centuries. Today, neckties are reduced to specialty occasion wear. Casual Fridays began in the 1990’s—the beginning of a preference for dressing down that never stopped. The demand for beautiful and innovative neckties design now comes from a smaller segment of sartorial-minded patrons globally who believe ardently in dressing well, which naturally includes the strip of fabric worn around the neck that projects a splash of individuality. An indirect, and potentially positive, trend created by the reduced popularity of neckties is that perhaps there are fewer “bad” ties produced nowadays versus the excessive abundances of yesteryear.

Thus, this enthusiastic contingent of connoisseurs continue to uphold the cherished traditions of expressive textile design found among the beautiful ties of past and present. The tie is widely considered the linchpin of the tailored ensemble and was historically the critical element in selecting a suiting material. This is still an integral practice in bespoke tailoring, and, as such, neckwear remains a thriving category among leading fashion houses such as Stefano Ricci, Hermes, Louis Vuitton, Ferragamo, Paul Stuart, Tom Ford, Caroline Herrera, and Paul Smith, among others.

Neckwear also includes bow ties, which have increased in popularity, especially among millennials. And although women comprise a much smaller group that wear neckties, they are certainly patrons as well.

Neckties appeared on women’s runways in 2022, and it will be interesting to watch if their inclusion has lasting power. It’s also a given that most of the neckwear design in the world has been designed by women, and, of course, women are primarily the chief buyers and gift-givers of beautiful ties.

NECKTIE PRODUCTION

Neckties were huge during their peak (circa 1920 to 1990) leading to weaving mills dedicated solely to producing tie cloths–both here in the United States and abroad, and continuing today in Italy, and to some extent, the United Kingdom.

Paterson, New Jersey was the early center for neckwear fabric weaving in the United States, though Allentown and Scranton, Pennsylvania were active as well. Early in the 18th century and first half of the 19th century, immigrants from the Macclesfield area in England brought weaving expertise to America, whose immigrant shoes were later filled by German immigrants from the Krefeld area and later into the early 20th century by Polish Jews from Lodz and Bialystok. Many of these weavers thrived into the late 20th century–Kalkstein Mills, Raxon (now owned by Vescom), Joseph Teshon, Cosentino Silk Mills, Petersburg Silk, Perini, American Silk, and MTL are the mills I recall who held core business interests in neckwear weaving.

The United States, Japan, France, Spain, Korea, and Switzerland, once renowned for silk weaving for neckwear and tie manufacturing, account for very modest outputs today. China dominates what is left of the lower to middle-tier necktie market. Little surprise that the high-end silk counts created for neckwear, and once employing silk, and to a lesser extent polyester, have remained active, but also employed for other uses such as upholstery, drapery, and wallcovering fabrics, though the silk has often been replaced with polyester and nylon. Only the tie fabric weavers who shifted the extra-fine end counts toward other opportunities in new markets survived. Mills with neckwear archives were able to translate many innovative necktie designs into upholstery, though many necktie designs were designed on a bias to accommodate necktie production based on the scales of their pattern repeats.

Translating such archives today, however, is much easier. Scanning and CAD tools are used to reconfigure new repeat and weave assignment as needed. Tasks that once took days can today take mere minutes. The less flexible mills who were unable to adapt to new markets and technology shuttered and are almost now forgotten outside historical society references. Currently, as chunkier plains and textures employing heftier warp and weft yarns dominate, the high sleigh constructions are again challenged to share their intricate detail to profitable markets.

Weaving-wise, it took great skill and numerous technicians to create elaborate point paper designs to be translated into hole-punched jacquard cards. There also existed an entire cottage industry supporting these weavers from dyeing to yarn-making as well as cutting jacquard cards to hanging jacquard harnesses. Much of this supportive layer of industry is now left to history, and even silk weaving is quite a rarity today for there is little demand for its dressy elegance in furnishings.

Entering the textile industry when I did, I witnessed the tail end of a brilliant run. The Fourth Edition of the Modern Textile and Apparel Dictionary by George E. Linton, PhD, Tex ScD, which was published in 1973, a decade prior to my finishing college, contains 41 sub-definitions under the Neckwear listing. Interesting to note here are some less prevalent weave terms used then such as: Amure Weaves, Barthea, Cannele, Foulard, Loisine, Mogador, Charvet, Rhadzimir, and Satin Faconne, amongst more popular construction terms still common in use such as Poplin, Challis, and Repp Weave. Interestingly enough, vintage neckties often called out the type of weave on a label such as “100% wool hopsack,” “Crepe weave,” and “Poplin – Loomed in America”.

NECKWEAR FABRICS & FIBERS

Neckwear is woven, printed, or knitted with a myriad of options within each category. Hand-painted ties were popular after World War I, but were replaced with more efficient production, printing, and weaving methods. Woven cloth constitutes more texture and heft and include tartans and plaids, colorful stripes—often ribbed or featuring insignias, as well as intricate jacquard-woven designs, ranging from dots and paisleys of every possible iteration to sophisticated geometrics and complex, often textural weaves. Some engineered designs are created that only work as a properly worn tie and extoll a powerful design statement with their singular focus. The indispensable solid ties can range from smooth and lustrous satins to chunky matte textures and everything in between. Specialty ties include denim, chambray, and even velvet. Prints are the most common tie design type and include anything imaginable from classic high design to comic relief.

The quality of the base cloth for the print as well as the given pattern’s design and color rendition offers endless possibilities. Generally, printed cloths can be less expensive than their woven counterparts to produce, however high-quality, hand-made printed ties are every bit as quality-oriented and distinguished as the best in woven ties. A quality tie is essentially made by hand, and there are numerous details that separate the bespoke-made from commodity mass production (see distinguishing details noted in the Necktie Glossary in the resources).

Knitted ties are not produced fully by hand like fine woven and printed ties; rather they are knitted into their slender form on a knitting machine, and sometimes referred to as crochet ties, offering a less dressy, but tactile uniqueness usually including a flat end. As with knits, there are endless combinations of colors and designs with the majority of knitted ties comprising silk or wool or a blend of each.

Naturally, silk is the most popular fiber for neckwear. Its uses range from lustrous and smooth material (simply perfect for tying a knot and draping beautifully) to raw silk and shantung renditions that portray a coarser reflection of this wonderous fiber. Polyester does a good job imitating silk, but, in the end, it will never match silk and its favor lies in the lower-priced or uniform market segments.

Wool ties hold a special place due to the matte colors, heft, and a scratchier hand which can pair well with certain cooler-weather garments. Fine worsteds and lambswool cloths provide a softer, more heathered personality alternative and are also popular. An upper tier of the market will employ cashmere for neckwear, which starts to bring neckties closer to scarves for their supple warmth. These fibers are not as hardy as other fiber choices and as such remain rarer in use. Cotton and linen are also valuable fiber players in neckwear that can be less dressy and offer a lighter weight for warmer climates. Interesting blends of the above fibers flourish and can really create some wonderful cloths.

Nylon is rarely employed due to its puddling character. Acetate was used commonly in the mid-20th century, but proved not to be as resilient as silk. Viscose only has made a modest inclusion, usually combined with silk for cost, and again because it cannot quite compete with silk for hand, performance, and aesthetic values. Of late, microfiber ties are available, but since neckwear fans today are more discreet, silk ties are typically the top choice.

GIVE A TIE A TRY

And like a very good cup of coffee, the average person can afford the luxury of top-tier neckwear fashioned by an international master if that is their wish, especially if pre-owned is an option. Case in point: Ebay and Etsy can make you dizzy with their sheer variety and quantity; however, focusing upon a particular designer matching your taste is the best approach. For example, Emilio Pucci is excellent for colorful abstract and psychedelic designs, while Missoni is amazing for the house’s signature modernist color and geometric plays. Christian Dior and Yves St. Laurent are good options to explore, offering a wide range of high caliber design from modern to traditional.

My hope is to refresh your outlook of neckwear–primarily neckties–and to invite exploration of the wide, diverse, and beautiful trove of almost endless designs that are certain to provoke inspiration and admiration, due to the sheer bounty on offer. Perhaps you will be inspired to wear neckwear anew: it’s a truly distinctive pleasure to wear a nice tie, and this little luxury has been forgotten by so many. It’s even a visceral sensation to unknot a tie after a day of wear–try it; you might like it. As the adage goes, even today, “It pays to look well.” And, lastly, food for thought. Perhaps neckties will follow a path similarly to their distant cousin, the vinyl record. Vinyl records 25 years ago were given away in the face of the superior CD format followed by digitized music, only to reemerge as the most popular medium for recorded music today. Go figure.